Chapter 3: Exploring Climate Data#

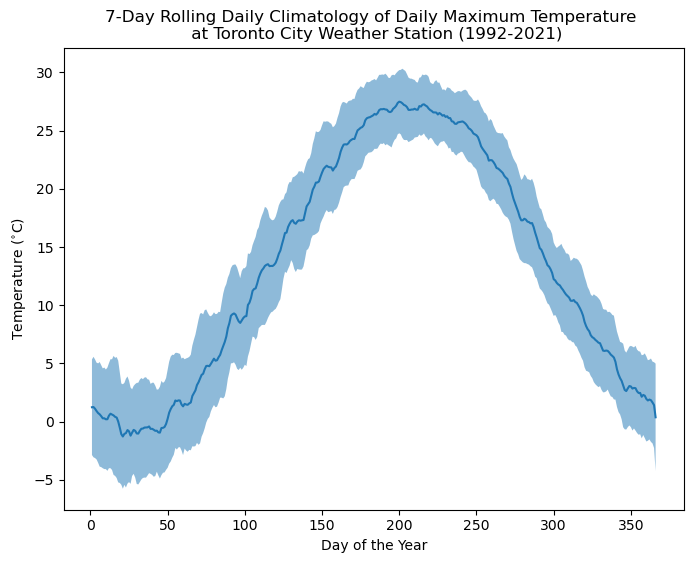

There are several types of climate data that are relevant and necessary for thorough climate change impact assessment. First and foremost is observational data, generated from either in-situ measurements like weather stations, or remote sensing of the climate system through satellites or radar. Observational data is a critical part of the downscaling and climate impact analysis workflow. Before you can even start to consider how climate change will affect a certain climate indicator related to your study domain, you need to understand what this metric looks like in the climate of the present and recent past. This includes things like the seasonal cycle - how the indicator (and/or climate variables used to calculate it) typically varies throughout the year - which we quantify using a climatology (also called climate normal). This is usually calculated using long-term (30-year) averages for each month, season, or day of the year, with a range of typical values, usually quantified using the one standard deviation range about the mean. Depending on your application, you may also be interested in extreme values of a climate variable or indicator - values that fall outside the typical range of variability. Of course, we also need observations to use in the bias-adjustment step of downscaling (more on that in Section 4), so there are many reasons why it’s important to learn how to acquire and analyze observational data. Section 3.1 will walk through the basics of downloading and analyzing data from Canadian weather stations managed by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), while Section 3.2 will explore similar procedures for gridded observational products which offer complete spatial coverage for an extended domain, very useful for downscaling applications.

|

|---|

Daily climatology of daily maximum air temperature at the Toronto City weather station, calculated from the long-term average of observations from 1992-2021. |

Next is synthetic data generated from numerical models. If gridded observations are not available for your study domain or for the variables you need, you may wish to use reanalysis (Section 3.3) as a proxy for observations to train your downscaling model. Finally, every downscaling study needs output from climate models (GCMs or RCMs). To quantify the model biases relative to observations and to establish the baseline climate, we need model output for a historical period that overlaps with when observations are available. In order to produce climate change projections, we also need model output for a future climate scenario, such as one of the RCPs (CMIP5) or SSPs (CMIP6), and for a particular future time period or level of global warming. Sections 3.4—3.6 will deal with downloading and doing basic analysis of climate model output.